The COVID-19 pandemic and the changes it has sparked have added new pressures to an already stress-prone profession.

In this article we hear from Helen Pamely, Partner at Rosling King, coach, wellbeing consultant and psychotherapist on how lawyers can get to grips with their ‘stress signatures’ and overcome them through mindfulness.

As we continue to grapple with the pandemic, the question of how we adapt to the ‘new normal’ in our working and professional lives is at the forefront of our concerns. As lawyers, we need to take particular note of this. Research suggests that legal professionals generally experience higher levels of depression, anxiety, stress and lower levels of mental wellbeing than members of the general population.

According to a recent study from legal mental health charity Law Care (entitled ‘Life in the Law’), the majority of participants surveyed (69%) had experienced mental ill health in the 12 months before completing the survey. Only 56% of them had talked about this at work, and the most common reasons given for this were the fear of stigma and the resulting career implications, and financial and reputational consequences. Among other things, the study also found that legal professionals were at high risk of burnout, with our juniors (aged between 26 and 35) displaying the highest burnout scores.

Having spent a decade in the legal profession, I unfortunately do not find these results particularly surprising. We work in a highly competitive profession, often with heavy workloads, tight deadlines and high expectations from both partners and clients. The above results point to issues which are arguably a reflection of the culture of our industry, and there is without doubt much which needs to be done to address this.

“Research suggests that legal professionals generally experience higher levels of depression, anxiety, stress and lower levels of mental wellbeing than members of the general population.”

But there are also things we can do to alleviate stress and pressure to stay mentally fit. The question we need to ask ourselves is: what can we do to maintain our sense of wellness and inner balance?

In my experience as a lawyer, coach and psychotherapist, it is helpful for us to understand and reflect on the following at the outset:

1. How stress works;

2. How to recognise our own personal stress indicators;

3. How mindfulness can help reduce stress and lay the foundation for a healthy, balanced lifestyle.

Understanding stress

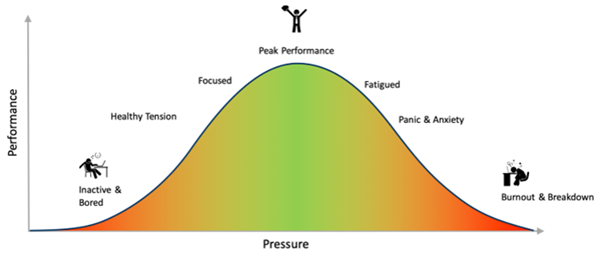

First and foremost, we need to acknowledge that stress is not all bad. It is our natural and normal reaction to a physical or emotional challenge. It can even be motivating. According to the Yerkes-Dodson Law, the relationship between stress and performance can be measured on a bell curve. It is only when stress goes beyond the peak of the bell curve that we suffer from stress-hormone-overload and performance suffers. Sustaining an overload for a long period creates imbalances in our nervous and immune systems, leaving us more vulnerable to illness.

As, we thrive in a fast-paced, challenging, dynamic working environment. We embrace sustained energising levels of stress to reach our potential and excel in our careers. But we need a mechanism to ensure our stress levels do not lower our performance; or worse, damage our mental and physical wellbeing. It can be hard to gauge when things are getting out of hand, particularly if we have a tendency towards feeling anxious or depressed in our normal life. This is why it is important to get to know our own personal stress indicators: our ‘stress signature’.

Knowing your ‘stress signature’

Our individual needs and strengths are balanced differently. There is no ‘one size fits all’. Common indicators of stress include (but are not limited to):

• Sleep disruption: struggling to drift off, waking up throughout the night;

• Feeling easily irritated;

• Having difficulty staying focused;

• Pulling away from colleagues, friends and family;

• Putting off things that need to be done, or conversely feeling as though everything must be done now;

• Developing unhealthy eating habits;

• Avoiding doing things which we know are good for us (e.g. running, working out, yoga, meditation etc);

• Increasing our use of alcohol;

• Turning towards addictive relaxants, e.g. cigarettes, benzodiazepines.

The question to ask yourself, therefore, is this: ‘What physiological and emotional responses do high levels of stress generate in me personally?’

First and foremost, we need to acknowledge that stress is not all bad. It is our natural and normal reaction to a physical or emotional challenge.

Mindfulness matters

The key is to learn to tune into our own mind and body. A great tool for this is mindfulness, which is the basic human ability to be fully present, aware of where we are and what we are doing, and not overly reactive or overwhelmed by what is going on around us. Mindfulness also provides us with an increased awareness of how we are feeling, which we might otherwise not have spotted.

If we can recognise our own personal ‘normal’, then we can learn to identify when we feel unbalanced and overly stressed before we spiral out of control. Equally, if we do feel overwhelmed, being mindful of our own ‘normal’ can help us take a step back and understand why. Mindfulness allows us the opportunity to do whatever is needed to help us feel well, whether by going for a walk, playing with our dog, practising yoga, taking a hot bath or giving ourselves some time to simply rest. For us lawyers, simply ‘being’ (rather than always being on the go and ‘doing’ things) can prove to be a real challenge!

By understanding our ‘stress signature’ and tuning into our mind and body using mindfulness, we can learn to take care of our wellbeing in a preventative and progressive manner and, ultimately, thrive in the face of whatever life throws in our path.

Ways to practice mindfulness

Practising mindfulness can take many forms, including meditation, deep breathing and guided imagery. The key is to realise that although the methodology behind mindfulness is simple, our active minds will seek many ways to resist and reject change. To overcome these obstacles, it helps when we grant ourselves the kind of patience and openness we show to a good friend. Practising mindfulness little and often, even five minutes a day, is enough to reap the benefits.

Example exercise

Why not try the exercise below? This can be used on a daily basis and acts as a great de-stressor as well as providing the groundwork for learning to tune into ourselves and identify our own ‘stress signature’.

1. Take a deep breath through your nose to the count of four, allowing your stomach to expand. Pause for two seconds. Exhale slowly through your mouth to the count of eight. Repeat eight times.

2. If you notice tension in your body, try non-judgmentally to notice this but not get caught up in it. Gently return your concentration to the breathing exercise.

3. Then ask yourself: what thoughts, feelings, emotions and bodily sensations are in your present-moment experience right now?

4. Allow a couple of minutes simply to sit with this question.

5. Allow whatever arises in response. Do not try to push it away or grasp onto it; just let it be.

6. When you feel ready, open your eyes.

7. You may wish to note down any particular insight you gained into the thoughts, feelings, emotions and bodily sensations noticed.

For further information, please contact Helen Pamely.